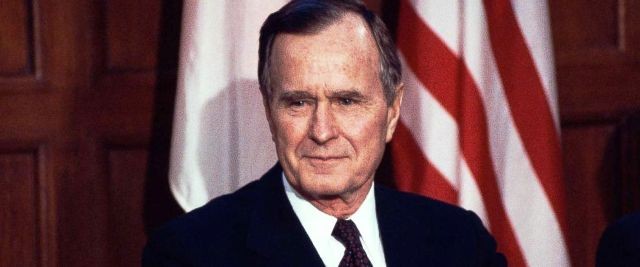

Very few Presidents in the history of the United States have been as experienced and trained to hold the highest office in the country as George H. W. Bush was.

A seasoned public servant and diplomat, he knew first hand how to manoeuvre in the meanders of the US bureucracy, the elaborate nexus of international institutions, and state interests. He had served in just about every post of significance before he was elected to the highest office of the land, becoming the 41st US President. He had served in Congress, the Central Intelligence Agency, as Ambassador to the UN and China, and as Ronald Reagan’s Vice President.

Not only did he know the world of politics and diplomacy but he had a penchant for picking the right people for the right posts, while avoiding the bureaucratic infighting that comes with strong personalities. From the indispensable James Baker to the quietly effective Brent Scowcroft, Bush’s team was formidable and functional.

His Presidency would need every bit of this expertise as it came in the midst of the most momentous events of the twentieth century. The end of the Cold War and the liberation of Eastern Europe, the reunification of Germany, the massacre in Tienanmen square and the first Gulf War.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the Bush administration had to deal with the German question. He outmaneuvered the Soviet leadership every step of the way convincing them to give up the military presence of 400,000 troops on German soil and any territorial claims. At the same time he dealt with the fears of a unified Germany among western allies.

The ‘four plus two’ negotiating formula unified Germany and anchored it in NATO and the West. Bush managed friends and foes skillfully. By avoiding victory laps and showing restraint towards the Soviets, and by consulting with and informing America’s allies of US intentions or major upcoming decisions. Eastern Europe was liberated, Germany was unified, and eventually, the Soviet Union itself disintegrated without bloodshed.

He did not have any time to rest on his laurels, however. In the midst of all this, Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait. Saddam saw a window of opportunity in a time of change to pursue his aggressive agenda in the Middle East. ‘This will not stand’ was Bush’s response. And it didn’t. International sanctions were followed by military action by an unprecedened international coalition, including Arab states, assembled skillfully by Bush.

It was the first post Cold War crisis that would bring US and the Soviet Union side by side creating premature hopes for a new world order of superpower cooperation. Saddam was rolled back from Kuwait but Bush stopped short from invading Iraq and getting enmeshed in the quicksand of regime change in the Middle East. Some pundits and neoconservative critics accused him of leaving behind unfinished business.

Nevertheless, Bush’s prudence paid off. The rules and norms of the international order were reaffirmed. The US emerged as a benign hegemon legitimising its power, interests, and world leadership through the mantra of international institutions and its adherence to international rules.

Bush’s domestic approval ratings skyrocketed to almost 90%. Having orchestrated a peaceful transition to the post-Cold War era, and having won the Gulf War no one would have expected that he would depart office as a one-term President. His nemesis was a young governor from Arkansas who successfully turned the public’s attention away from Bush’s international triumphs to a weak economy with the telling slogan, ‘it’s the economy stupid’.

Bill Clinton reminded Bush that international triumphs may build legacies but economic records win elections. It was a lesson Clement Attlee had also taught Winston Churchill after the Second World War.

Years later, part of Bush’s international legacy would come into question. The neocons would convince the 43rd President, the younger Bush, after 9/11, to finish the job his father had left incomplete. Bring an end to Saddam’s regime and the axis of evil and engage in an ambitious project of democratization of the Middle East. Sadam was ousted from power and brought to justice but subsequent developments in the region rather pointed to H.W. Bush’s prudence and strengthened his legacy.

Bush did not have a Wilsonian vision of a new world order, confessing in a self-deprecating manner, that ‘he was not good with that vision thing’. But he didn’t ‘go wobbly’ as Margaret Thatcher feared. He was a pragmatic leader that managed change skillfully at a time that events were unfolding rapidly.

He did so by being deferential to his allies and magnanimous and modest to the defeated. By building alliances and coalitions as well as by avoiding unnecessary friction and conflict. He did it by being prudent.

A weak economy and a broken promise on not raising taxes cost him the election to a second term. It was an inglorious end to an illustrious career of public service.

www.martenscentre.eu/blog